ALMOST EVERYONE, barring the inevitable elitist bores blinkered by their own super-hipness, seemed to have a soft spot for Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. In late ’77, Rolling Stone even ran an absurd piece attempting to work out the whys and wherefores for the album’s astounding success, only to waste several thousand words of piffle concluding that it was, in the words of Warners’ Derek Taylor, “simply a very, very good two-sided pop record.”

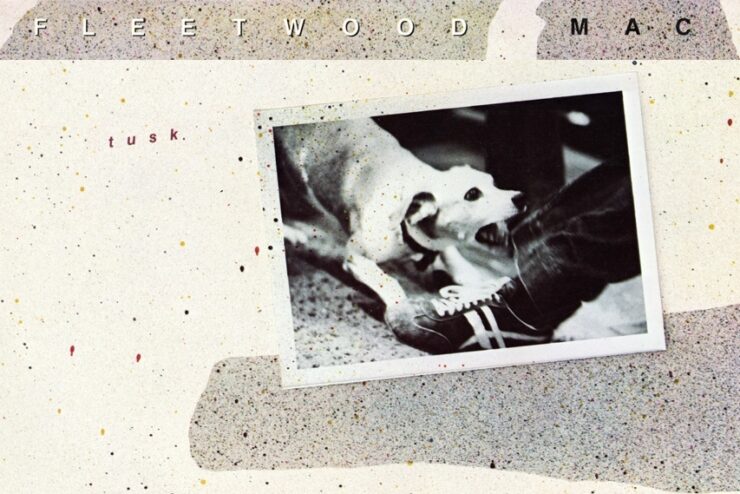

Tusk, a long time in the making, is by and large a good four-sided pop record. It’s no untarnished masterpiece, of course, but a highly adventurous gamble for much of its playing time, and certainly not just another coldly precise and pristine work.

In retrospect, although the fact didn’t impinge on the listener, the contents of Rumours were housed within a framework, that being the very real breakdown of relationships within Fleetwood Mac, the traumas experienced thereby and the need to come to terms with a then newly gained independence, all of which were apparently occurring during the album’s recording. But now some three years have passed since then and Tusk, bereft of such a stormy emotional centrepoint, can clearly zero in on the diverse compositional talents of the group’s three songwriters, Christine McVie, Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham.

When this incarnation of Fleetwood Mac was ushered into the public eye with the Platinum ice-breaker Fleetwood Mac, of the three composers involved in the enterprise it was the two ladies who shone. Although prolific, Buckingham seemed unable to match their standards, to the point where his songs lacked clout, sounded anonymous and appeared mere fillers.

But Buckingham mustered his resources for Rumours and cuts like ‘Go Your Own Way’ were amongst the album’s high-points. Now on Tusk he’s become responsible for the largest output, clocking in a sturdy nine songs to McVie’s six and Nicks’ five. A ‘Pure pop’ purveyor, his work reeks of the influences of The Beatles, Beach Boys and Byrds, although he does manage to twist these tips of the pen to forceful effect.

After the set’s opener, McVie’s sparsely melodic “Over And Over,” Buckingham artfully breaks the potential preciousness of mood by throwing in a naggingly jaunty hoe-down of a rocker in the Carl Perkins tradition replete with effective loopy tweaks and a thick buzz-saw guitar sound worthy of Dave Edmunds entitled “The Ledge,” which could easily fit into Rockpile’s repertoire. McVie immediately responds with a smooth rocker, ‘Think About Me’, which, with Buckingham’s raunchy guitar phrasing very much in the Keith Richards tradition, is to pop what ‘Tumblin’ Dice’ was to rock.

Buckingham is all over the album, in fact, and his presence as a composer, producer and/or guitarist continually helps to keep everything diversified yet unified in its buoyancy. “What Makes You Think You’re The One” is an effective, lightweight and jokey slice of raucousness, not unlike some of The Beatles White Album frivolities. His Beach Boys debt is all too obvious in “That’s All For Everyone,” which features a gorgeously floating and incandescent coda that makes for the finest Brian Wilson music never written since “Sail On Sailor.” “Not That Funny,” on the other hand, is a Cajun-style bruising thump-up with a fade-out all too redolent of more White Album idiocies.

Buckingham’s finest moments occur on side three with “That’s Enough For Me,” a thrillingly dervish-fast blues rocker powered by Mick Fleetwood’s wicked bass drum mule kick and Buckingham’s sawing electric rhythm guitar underpinning a dazzling display of ragtime guitar picking. Finally, at the end of the side, Buckingham reshapes all the melodic power of “Go Your Own Way” into “I Know I’m Not Wrong,” a driving piece of rock action building to an infectious climax that mates The Byrds’ “Lady Friend” coda with all the bollocks of Sex Pistol-like multi-guitar power.

As important as Buckingham’s compositions are to Tusk, his production work helps to maintain an ever-effective spartan feel – only the essentials, with the odd embellishment carefully etched in for maximum impact – whilst his guitar playing continually impresses by dint of its virtuosity without ever being too flashy.

This feel is of paramount importance, particularly when faced with Nicks’ songs. If Patti Smith didn’t so desperately want to be a man and had a real comprehension of what makes for good musical structure, then she might well be Stevie Nicks. More to the point, even when her songs are obviously well constructed and lyrically intriguing, one continually gets this distinct image of Nicks as a young woman who played Ophelia at some high school production of Hamlet and never quite recovered from the experience. With “Rhiannon,” her dalliances with the supernatural were interesting and musically potent, but since then this infatuation with her dream-like enigmatic self as some extra-terrestial being touched by the whims of the muse’s wand has become just too precious to stomach.

“Sara,” for example, is a perfect example of this aspect of her writing and it’s becoming overbearing. Blessed by an ability to build attractive chord progressions, Nicks walks a thin line between what’s beguiling and what’s babble. Fortunately she has the musical wherewithal to paint an aural landscape on “Storms” that is genuinely affecting due mainly to the intimacy of the production at hand, whilst ‘Angel’ has a kick to it, a verve that keeps it lively and listenable. Her obvious piece de resistance “Sisters Of The Moon” is more heavenly wanderlust, made palatable by Buckingham’s blazing guitar holocaust.

Christine McVie is far more earthbound, and her six love songs are simple, pleasing paeans to the tender trap. Hers are woman’s songs that lack the self-consciousness of Joni Mitchell’s former odes to sweet surrender, say, and at their best, as in the hauntingly beautiful “You’ll Never Make Me Cry” and the seductive coda of “Brown Eyes,” make for quintessential adult pop music.

Dealing with the three composers separately, it’s all too easy to forget Fleetwood Mac as a group which, if nothing else, Tusk is testament to. Fleetwood’s drumming is an exercise in precision and sympathy, whilst bassist John McVie is so good you don’t even notice him.

Ultimately it’s time to stop bracketing Fleetwood Mac alongside Foreigner, Boston, Linda Ronstadt, The Eagles, etc, in the same way that reactionaries bracket together The Clash, Human League, pragVec, The Slits and Elvis Costello.

Fleetwood Mac make good, adventurous “pop.” As Charles S. Murray said of Joe Jackson, if you reckon you’re too hip for Tusk, then you’re simply too hip.

© Nick Kent / NME / October 20, 1979